The last ten days or so I’ve spent at CERN testing new designs of pixel detectors for the ATLAS experiment. Since it was the IOP’s #iamaphysicist event on the same day we were setting up, I tweeted out the following picture.

To measure our pixel detectors, we need a beam of particles from a particle accelerator. Fortunately at CERN, we have many to chose from! Just see the diagram of all of the accelerators required to get the protons to the LHC. Our experiment uses the SPS, or Super Proton Synchrotron, the last accelerator in the chain of accelerators which feed the LHC with protons. The protons enter the SPS at 25 GeV and are accelerated up to 450 GeV (note the LHC accelerates to 7500 GeV, or 7.5 TeV, per beam). We then use a target to change the type of particle from a proton to a pion.

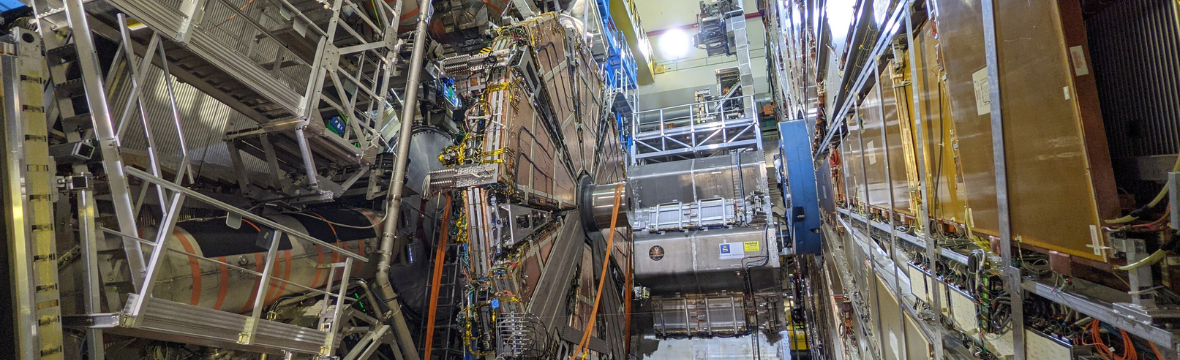

Since these detectors are very new, we need a reliable way to understand how well they’re working. For this, we use a telescope. I’m not talking about a long brass tube with curved glass inside to look at the stars. In our case, a telescope is a series of planes of reliable detectors which will measure the charges particles. The new and interesting detectors we want to study go in the middle. We use the telescope planes to measure the position of charged particles as they go through our setup and later we can reconstruct the tracks of the particles. This allows us to know where the particle should have hit our new device and we can look to see if it did. We can also study how the charge is shared with pixels that neighbour it.

Why do we do this? Well, before we spend a lot of time and money on building a new tracking detector, we should test how the devices work in a similar environment. This is especially true for later on in the detector’s lifetime – will they work as we expect them to for as long as we need them to? For this, we need to irradiate the detectors in one of the many facilities around the world. The detectors become a little damaged through the irradiation in a similar way to many years of use inside ATLAS, so we can test after ‘3 years’, ‘5 years’ and so on.

To do these measurements we have to make the most of the time allocated to us, so we split into shifts of at least two people to take data 24-hours a day. I ended up do a number of night shifts over the week, which allowed me to snap some photos of the CERN deer.

I also found this road sign when walking back from lunch one day, which made me think of a popular TV show:

After our time is over, we hand the experimental setup to the next set of users; there are a lot of groups who want to study their detectors in this way. Then, for us, the many, many gigabytes of data we collected need to be analysed, understood and written up to present to our colleagues. Indeed for the first half of this coming week, I’m at a workshop taking place in Italy to discuss results about irradiated detectors. Many of these results will have come from test beam experiments, although probably not the one from the last week.

Super interesting!! So what are the results? Would your current pixel detector prototype withstand 5 years ?

Thanks! 🙂

In our group we didn’t test any irradiated prototypes (which tells us how well they will work after a certain amount of time in ATLAS), and we haven’t finished analysing the data yet so we can’t say much for sure until we do. One didn’t work and we’re investigating why. Sometimes this is more interesting than the ones that do, because we learn more this way.